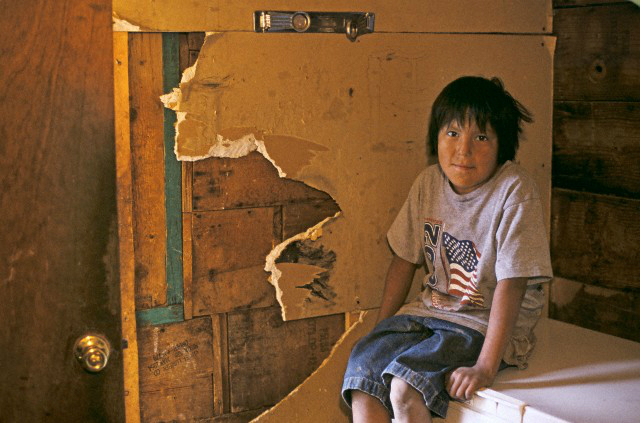

Laurynn Whiteshield was a happy, playful child who loved being with her family, “a family she knew loved her.” At least that’s what it says in her obituary.

Laurynn spent most of her life in a home where she was loved and protected. From the time she was nine months old, she and her twin sister, Michaela, were raised by Jeanine Kersey-Russell, a Methodist minister and third-generation foster parent in Bismarck, North Dakota.

When the twins were almost three years old, the county sought to make them available for adoption. But Laurynn and Michaela were not ordinary children. They were Indians.

And because they were Indians, their fates hinged on the Indian Child Welfare Act, a federal law passed in 1978 to prevent the breakup of Indian families and to protect tribal interests in child welfare cases.

The Spirit Lake Sioux tribe had shown no interest in the twins while they were in foster care. But once the prospect of adoption was raised, the tribe invoked its powers under ICWA and ordered the children returned to the reservation, where they were placed in the home of their grandfather in May 2013. Thirty-seven days later, Laurynn was dead, thrown down an embankment by her grandfather’s wife, who had a long history of abuse, neglect, endangerment, and abandonment involving her own children.

Laurynn was a victim of the law’s good intentions gone bad, said Kersey-Russell, who is once again raising Michaela. “There’s no fighting ICWA,” said Kersey-Russell. “I have a very strong ethic that says my job is to take care of children who are hurt and injured. It will hurt me. It will break my heart. But it is best for them. And I wish that ICWA would have the same heart.”

Good Intentions, Gone Bad

The Indian Child Welfare Act was passed with good intentions. Throughout much of the 20th century, Indian children were removed from their homes, often without good reason, and placed with non-Indian families or in boarding schools where they were indoctrinated into the Anglo culture, according to congressional findings.

But critics say the law has morphed into a tool to protect tribal power at the expense of Indian children, who are at greater risk of remaining in abusive homes because of the maze of rules that apply only to Indians.

The most glaring shortcoming in the statute is that it does not explicitly protect the best interests of the children, which has been the guiding principle in state child welfare laws in the United States for more than 200 years.

Unlike other children in America, an Indian child’s best interests is not specified as the determinative factor in decisions about parental rights or child placement. ICWA puts the rights of Indian tribes on par with those of the children and parents.

The law is “a means of protecting not only the interests of individual Indian children and families, but also of the tribes themselves,” the U.S. Supreme Court said in a 1989 case, the first of only two involving ICWA the high court has considered.

Tribes define who is an Indian child eligible for membership. Parents challenging severance of their custodial rights can, and often do, join the tribe after the court case has begun, giving them what the Supreme Court recently called a “trump card” to derail adoption proceedings.

Some tribes, including the Cherokee Nation, have no blood quantum requirements, which refers to the amount of Indian ancestry an individual has. That means even a child with little or no Indian heritage can be a tribal member subject to the law.

The Cherokees are the largest Indian tribe in the United States.

There also is no requirement in the law that the child or the parents live on a reservation or have any significant connection with a tribe.

In the most recent U.S. Supreme Court case involving ICWA, decided in 2013, the child named Veronica Maldonado was only 1.2 percent Cherokee. Her nearest full-blooded Indian ancestor lived during the time of George Washington’s father, nearly 300 years ago, according to oral arguments in the case.

Neither of Veronica’s parents had lived on an Indian reservation or had any significant involvement with the Cherokee culture.

Yet because of ICWA, it took years of court battles before the adoptive parents, who were present at Veronica’s birth and raised her for more than two years, were able to adopt her.

In the end, the Supreme Court used a technicality to side with the adoptive couple. Since the biological father who challenged the adoption had abandoned the mother during pregnancy and after Veronica’s birth, he never had “continued” custody, the court ruled.

Several of the justices raised concerns about the constitutionality of the law, especially when applied to a child with so little Indian heritage and no connection to the tribe.

“Is it one drop of blood that triggers all these extraordinary rights?” Chief Justice John Roberts asked during oral argument.

That points to the fatal flaw in the statute, said Dr. William Allen, founding member of the Coalition for the Protection of Indian Children and Families and a critic of the law.

It all comes down to race.

“I would go so far as to call the legislation a policy of child sacrifice in the interests of the integrity of the Indian tribes, meaning the end has nothing to do with the children,” said Allen, former chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “It has everything to do with the tribe. To build tribal integrity, tribal coherence, the law was passed in spite of the best interests of the children.

“You can’t permit something like tribal sovereignty, any more than state sovereignty, to trump the fundamental rights of American citizenship. The rights are individual rights. They are not collective rights. And you cannot sacrifice the individual rights for the point of collective identity.”

‘PRESUMED’ BEST INTERESTS

But the Indian Child Welfare Act’s foundation is that the child’s rights can be sacrificed to protect the collective identity of the tribe.

Indian tribes were dying because their children were being lost, according to congressional testimony leading up to the passage of the statute in 1978.

Thousands of Indian children were being taken from their homes by state social workers and judges who mistook the rampant poverty and cultural differences on many reservations for child abuse and neglect.

In passing ICWA, Congress declared it is the “policy of this Nation” to protect the best interests of Indian children and promote the stability of Indian tribes by imposing minimum federal standards for the removal of Indian children from their biological families. The law also is meant to ensure that when abused children are taken from abusive parents they are placed in foster or adoptive homes that “reflect the unique values of Indian culture.”

ICWA created a labyrinth of special rules for dealing with Indian children that are meant to work in tandem with child protection laws in states, which historically had complete jurisdiction over child welfare proceedings. The law does not apply in custody disputes between biological parents. But if the state seeks to sever or interfere with an Indian parent’s custodial rights, either by putting the child in foster care or up for adoption, ICWA must be followed.

To terminate an Indian parent’s custodial rights, it must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that leaving the child in the home is likely to result in “serious emotional or physical damage.” That standard of proof is the same as in criminal cases. It is much higher than the clear and convincing standard of evidence typically used by state courts in child welfare cases involving non-Indians.

For any Indian child living on a reservation, the tribe has exclusive jurisdiction over child welfare cases.

For those living off the reservation, tribes have concurrent but presumed jurisdiction over state courts. That means state judges must transfer the case to tribal court unless there is “good cause” not to, or one of the parents objects.

Good cause is not defined.

The law also created a preference order for adoptions. Unless good cause can be shown to deviate, attempts must be made to place the child first with extended family members, then with other members of the Indian tribe, and then with other Indian families.

Only then can non-Indian placement be considered.

Again, good cause is not defined.

Non-binding guidelines published by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs in February say courts should not consider the best interests of the child in determining foster care or adoptive placements. Placement in an Indian home is presumed to be in the child’s best interests.

The law also forbids judges from blocking placement in an Indian home based on poverty, substance abuse, or “nonconforming social behavior” in a particularly Indian community or family, according to the BIA guidelines. That can force children with even a slight Indian heritage into environments where poverty, crime, abuse, and suicides are rampant.

Indian children suffer the second-highest rate of abuse or neglect of any ethnic group, behind African Americans, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The child maltreatment rate for American Indians and Alaska Natives is about 50 percent higher than for white or Hispanic children.

Indians also have the second-highest rate of homicide deaths and infant mortality, behind African Americans.

Indians have the highest suicide rate in the nation, according to the CDC. The suicide rate for Indians 15-34 years old is 2.5 times higher than the national average. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for that age group.

Also, Indians have the highest rates of gang involvement and poverty of any ethnic group, according to federal reports.

Nationwide, about 27 percent of American Indians and Alaskan Natives live in poverty, almost twice the national rate, according to census data from 2007 through 2011.

Indian children experience post-traumatic stress disorder at the same rate as veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, and triple the rate of the general population.

“Today, a vast majority of American Indian and Alaska Native children live in communities with alarmingly high rates of poverty, homelessness, drug abuse, alcoholism, suicide, and victimization,” an advisory committee created by former Attorney General Eric Holder to study violence against Native American children said in its November 2014 final report.

“Domestic violence, sexual assault, and child abuse are widespread,” the co-chairs of the committee said in the report’s cover letter. “Continual exposure to violence has a devastating impact on child development and can have a lasting impact on basic cognitive, emotional, and neurological functions. We cannot stand by and watch these children—who are the future of American Indian and Alaska Native communities—destroyed by relentless violence and trauma.”

The committee recommended more money and autonomy for Indian tribes.

David Simmons, government affairs director for the National Indian Child Welfare Association, a pro-ICWA advocacy group, said it is unfair to use white, middle-class standards to judge Indian parents. Poverty and crime are rampant in many areas on and off Indian land, but that does not mean individual families in those areas would not make good parents, he said.

“There are many communities that have a lot of these challenges,” Simmons said. “It doesn’t mean that every family in that community is exposed to that same level of social problem, and it doesn’t mean that every community within tribal lands has the same level of that problem either. I trust that tribal communities make good decisions about where to place their children.”

NUMBERS UNKNOWN

There are no national figures on the number of children affected by ICWA. The U.S. Administration for Children and Families, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, has proposed rules to allow it to begin collecting data specific to the law, but has not yet begun that process.

On Sept. 30, 2013, there were 8,652 Native American children in foster care, about 2 percent of all children in foster care nationwide on that date, according to the most recent statistics from ACF. That represents a one-day snapshot since children move in and out of the system over time.

In the 2013 fiscal year, 5,465 American Indian and Alaskan Native children entered foster care and 4,758 exited the system for various reasons that include reunification with their parents, adoption or reaching the age of emancipation.

There were 1,805 Native American children awaiting adoption on Sept. 30, 2013.

Native Americans have the highest rate of children in foster care of any ethnic group, about 13 children per 1,000. That is almost three times the rate of white and Hispanic children.

There also is no way to know how many Americans could be subject to the act since its application varies based on the membership requirements of individual tribes. Some require a minimum percentage of Indian or tribal blood. Others do not.

There are almost 4 million people who are solely American Indian or Alaskan Native living in the U.S., according to current Census Bureau estimates. That number rises to about 6.5 million when Native Americans of mixed race are included.

To be considered Native American, individuals should maintain “tribal affiliation or community attachment,” according to the census definition. There is no such requirement in ICWA.

A study published in June by the Pew Research Center indicates millions of other Americans could be affected by the law, even though they do not consider themselves Indians and tend not to report their mixed heritage to the census.

About 6.9 percent of American adults are of mixed race, Pew found. Of those, about 68 percent report having an Indian parent or grandparent.

Matching Pew’s findings against census data indicates more than 11 million American adults have at least one grandparent they identified as Indian.

A person with one full-blooded Indian grandparent would be one-quarter Indian. That is enough to qualify for membership in many tribes.

Since the Pew study traces the lineage of adults, and does not address percentages of Indian blood, there is no way to estimate how many of their children might fall under the dictates of the statute. Also, blood quantum requirements vary by tribe, so a child who is one-quarter Indian may qualify for membership in one tribe but not another.

Mixed-race Americans with Indian blood also tend to have few ties with Indian culture. Only 22 percent of those with a mix of white and Indian backgrounds say they have a lot in common with Indians, according to Pew. Among those with black and Indian ancestors, 13 percent say they have a lot in common with Indians.

An Indian child under ICWA is defined as being either a member of an Indian tribe or the biological child of a member of an Indian tribe who is also eligible for membership.

While the definition sounds simple, its application in the real world is not.

‘LIKE A DEATH’

Laura and Pete Lupo lost “Elle,” a three-year-old child they raised as foster parents then sought to adopt, due to that definition.

Elle’s mother was a drug addict. Her father was in prison, serving time for assault with a deadly weapon.

The girl was 14 months old in June 2012, when Washington state child welfare workers dropped her off. She was dirty and bruised, and brought nothing with her but a pair of ill-fitting pajamas and a pacifier.

The Lupos of Lynden, Washington, were told it would likely be a short-term placement while the mother struggled with her drug habit, Laura Lupo said.

But the rehabilitation efforts failed and in December 2013, the state moved to terminate the mother’s parental rights, which would make Elle available for adoption.

Laura Lupo, a school counselor, and her husband, a teacher, were told by the social worker they would be the ideal placement for adoption.

That’s when Elle’s uncle, the father’s brother, challenged the adoption under ICWA. Elle was less than 2 percent Cherokee, but that was enough to make her an Indian child and to invoke the law’s placement preferences.

“As soon as the tribe became involved, everything flipped around and it was basically a done deal at that point,” Laura Lupo told the Goldwater Institute.

State child protective workers immediately went from touting the Lupos as the ideal adoptive parents to insisting they had no rights and Elle should be placed with her uncle.

The Lupos tried to fight, initially in court and later by taking their case to the media.

Laura Lupo said their public battle for custody of Elle made them the targets of threats and intimidation, both from activists on social media and by the state. Their jobs were threatened, and the state eventually yanked their foster care license for going public.

All their efforts failed in June 2014, and Elle was sent to live with her uncle.

Since then the Lupos have heard nothing about the little girl they took care of for two years, other than a brief interview the uncle gave to a Seattle television station.

Losing Elle has “been like a death,” Laura Lupo said.

“It’s been really difficult, and it’s a helpless feeling because we can’t do anything,” she said. “It’s hard not knowing how she’s doing. That bothers me a lot. It’s like ‘poof. She’s gone. That’s the end.’

“They made it a race issue and it was never, ever about that. I don’t care if she’s white, red, black, or green. She’s a little girl and we love her.”

Paul and Jena Clark of Phoenix spent three years and $300,000 fighting in Iowa courts to keep their adoptive daughter, Lauren, who was called Nairobi when she was born to a part-Indian mother in 2006.

Lauren’s birth mother, Shannon, selected the Clarks as Lauren’s adoptive parents before she was born. Though she lived on non-Indian land in Iowa, Shannon was a member of the Tyme Maidu Tribe of California.

The tribe initially agreed to allow the Clarks to adopt Lauren, telling them they were an ideal family. Paul Clark is a Navy veteran and commercial real estate broker who spent 20 years coaching youth sports. Jena is a school teacher.

But shortly after Lauren was born, the tribe intervened and demanded she be returned for placement in an Indian home. It claimed that power under both the federal law and a separate Iowa state statute that made it even more difficult to place an Indian child in a non-Indian home.

The case dragged on for three years, eventually reaching the Iowa Supreme Court, which declared the state statute unconstitutional because it deprived Shannon of her rights as a custodial parent to determine what is best for her daughter. Shannon always insisted the Clarks should be the ones to raise Lauren.

The federal statute still applied and the case was sent back to lower courts for another year. Eventually the tribe settled and allowed the Clarks to adopt Lauren.

“Financially it buried us,” Paul Clark said. “The tribe in our case had a casino and they had unlimited funds at their disposal. For us as a family, it sucked our accounts dry.”

The worst part though, was knowing they could lose Lauren at any time, Jena Clark said.

“It was a constant worry that we were going to lose her,” she said. “Paul, he’s a fighter and I was like ‘you need to make sure we don’t lose her because that would destroy our family.’ I was like, can they do this? Can they just take her? Can they just come and get her some day without any rhyme or reason? That was a big fear.”

Brandi Peterson of Dexter, Kansas, went through a similar ordeal after she and her husband arranged to adopt a child with less than 1 percent Indian blood.

The birth mother, whose grandfather had enrolled her in the Cherokee Nation when she was born, selected the Petersons as the adoptive parents shortly after becoming pregnant.

Journey was born in August 2010.

The Cherokee tribe invoked ICWA and intervened in the case in October 2010, challenging the adoption by the Petersons and insisting the child be placed with a tribal family.

The Petersons had no money to fight the tribe but did get financial support from their church. They also had the advantage of the birth mother insisting she would never agree to tribal placement, and that she would revoke her consent to put Journey up for adoption if she was placed with anyone but the Petersons.

Eventually the tribe backed down and allowed the adoption to go through. Brandi Peterson said she was never told why.

Those were harrowing months, she said, not knowing whether the child they’d raised since birth and whom they loved as their own would be taken from them and placed in a distant Indian community with people she’d never met.

“It was kind of like she had a sickness and you didn’t know if she was going to survive or not,” Peterson said.

Politics or Race

TWO SETS OF RULES

The Indian Child Welfare Act was written to protect the cultural identity and heritage of Indian tribes. Whether it does that at the expense of the rights of Indian children has caused sharp divisions in state courts, where child welfare battles normally play out.

At the core of the constitutional controversy is the heightened procedures under the federal law that apply only to Indian children.

Essentially, ICWA creates a two-tiered system for protecting endangered children, one for Indians and another for non-Indians, according to constitutional challenges that have been filed in state courts across the country.

If a non-Indian child is removed from a dangerous home, decisions about parental rights, custody, and adoption placement are dictated by state laws alone. While most states have provisions to protect parents’ rights and to place children with relatives, they are secondary to the determination of what is in the child’s best interests.

Not so with ICWA. Aside from its omission of an explicit best interest requirement, the statute grants tribes and noncustodial parents rights that are not found in state laws.

Because of the higher standard of proof, it is much tougher to remove an Indian child and terminate the custodial rights of an Indian parent. That means an Indian child is more likely to be left in a dangerous home.

Many Indian cultures do not recognize the concept of terminating parental rights, regardless of past abuse.

Because there is a shortage of qualified adoptive homes, both Indian and non-Indian, the preference for placement with Indian families means Indian children will spend more time in foster care, critics of the law say.

A report published in 2010 by the Minnesota Department of Children and Family Services, which was investigating racial disparities in child welfare cases, showed 25 percent of Indian children eligible for adoption were placed in permanent homes within two years. That is the lowest of any ethnic group and less than half the percentage for white children.

Those factors combine to give Indian children fewer safeguards in child welfare cases, violating their rights to due process and equal protection guaranteed in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, according to legal briefs filed in the most recent Supreme Court case.

“What makes this child an Indian child here; it’s biology,” Paul Clement, the lawyer representing Veronica Maldonado’s interests in the 2013 Supreme Court case, said during oral argument. “It’s biology combined with the fact that the tribe, based on a racial classification, thinks that somebody with 1 percent Indian blood is enough to make them a tribal member, eligible for tribal membership.

“And as a result of that, her whole world changes and this whole inquiry changes. It goes from an inquiry focused on her best interests to a focus on the birth father and whether or not beyond a reasonable doubt there is a clear and present danger.”

POLITICS OR RACE

Advocates of the Indian Child Welfare Act say it is not about race. Rather, it has to do with the political status of sovereign tribes.

Race-based laws typically run afoul of constitutional protections ensuring equal treatment unless they serve a legitimate and vital government purpose. In those instances, they are supposed to be narrowly tailored to ensure they only remedy the particular harm that is targeted.

But Indians have historically been treated differently because of their tribes’ status as sovereign nations, similar to but not quite the same as states.

Defenders of the law rely on a 1974 U.S. Supreme Court case, Morton v. Mancari. The court ruled Indian hiring preferences were permissible at the Bureau of Indian Affairs because they served a legitimate purpose of giving Indians more control of their own self-government, declaring the preferences were based on political affiliation and not race.

That same argument is used by tribes in defending ICWA: that the heightened requirements are needed to protect the tribes as political entities and not to enhance or diminish anyone’s rights based on race.

Because of that, it is irrelevant how much Indian blood a child has.

Charles Rothfeld, a lawyer who represented Veronica Maldonado’s Indian father at the Supreme Court, said opponents use contradictory arguments to challenge ICWA. For example, critics claim the law is based on race, yet they also argue Veronica’s 1.2 percent Indian heritage is not enough to qualify her as an Indian.

“You can’t have it both ways,” Rothfeld, founder and co-director of the Yale Law School Supreme Court clinic, told the Goldwater Institute. “You can’t say the whole thing is unconstitutional because it’s racial, and then say it’s not racial enough because the child is only 1.2 percent. The fact is what defines tribal membership is the tribe’s own determination, its citizenship requirements.”

Citizenship requirements vary by tribe. While the Cherokees have no blood quantum requirement, other tribes do. The Navajo Nation, the second-largest American Indian tribe, requires a one-quarter bloodline to qualify for membership.

The flaw in the argument that ICWA is based on political affiliation with the tribe is that the criteria for affiliation comes down to race, said Mark Fiddler, who helped represent the couple seeking to adopt Veronica at the Supreme Court.

“The only basis for the child becoming politically eligible was racial connection,” Fiddler said.

Supreme Confusion

JURISDICTIONAL TRAUMA

The Supreme Court has not resolved the constitutional issues, either in the Veronica Maldonado case or an earlier 1989 decision.

The earlier case, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, was largely a dispute over whether tribal or state courts have jurisdiction over adoption proceedings involving children born to Indian parents.

Both parents were enrolled in the Choctaw Nation and lived on the reservation. When the mother was about to deliver twins, the parents drove to a hospital 200 miles away so the children would be born off Indian land. They wanted to escape the tribe’s jurisdiction and have the adoption handled in state court.

Two weeks after the twins were born, the parents signed papers allowing the children to be adopted by Orrey and Vivian Holyfield, a non-Indian couple.

The Supreme Court sided with the tribe, ruling that since both parents were tribal members and lived on the reservation, tribal courts had jurisdiction over the children.

Justice William Brennan, writing for the 6-3 majority, acknowledged the twins had lived with the Holyfields for more than three years at that point, and that the court’s ruling may not be what was best for them.

“It is not ours to say whether the trauma that might result from removing these children from their adoptive family should outweigh the interest of the Tribe—and perhaps the children themselves—in having them raised as part of the Choctaw community,” Brennan wrote. “Rather, we must defer to the experience, wisdom, and compassion of the Choctaw tribal courts to fashion the appropriate remedy.”

In the dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens raised due process concerns, stating that forcing the parents into tribal court against their wishes “closes the state courthouse door.”

Ultimately, the tribal court returned the children to the Holyfields.

Despite that, Justice Antonin Scalia, who voted with the majority, said in a 2012 television interview that the Holyfield decision was the toughest of his career.

“We had to turn that child over to the (tribal) council,” Scalia said. “I found that very hard. But that’s what the law said, without a doubt.”

‘LIP SERVICE’

The 2013 Supreme Court case, Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, touched more directly on the issues of race and tribal sovereignty because Veronica had no connection with the Cherokee Nation other than her 1.2 percent Indian blood.

Veronica’s Hispanic mother, Christinna Maldonado, and part-Indian father, Dusten Brown, lived in Oklahoma but not on Indian land when she became pregnant. Brown was a registered member of the Cherokee tribe, but beyond that had no significant involvement with the tribe, according to court records.

Brown was in the Army. He and Maldonado were engaged, but grew apart after she told him she was pregnant in January 2009.

Six months later, Brown agreed to relinquish his parental rights rather than pay child support.

He did not provide financial support to Maldonado during pregnancy, was not present when Veronica was born, and did not request visitation until she was 22 months old and the custody battle had already begun.

Meanwhile, Maldonado arranged for Veronica to be adopted by Matt and Melanie Capobianco, a South Carolina couple who had no children.

Veronica was born in September 2009. The Capobiancos were in the delivery room, and Matt cut the umbilical cord. Three days later, they filed the paperwork in South Carolina state court to adopt Veronica.

In January 2010, a few days before Brown deployed to Iraq, he signed the paperwork consenting to Veronica’s adoption.

That, coupled with his failure to provide any financial or emotional support to Maldonado during pregnancy, would have ended the matter under state law.

But not under ICWA.

Brown changed his mind almost immediately and challenged the adoption in state court with the assistance of the Cherokee Nation.

The South Carolina courts sided with Brown, ruling he did not voluntarily relinquish his parental rights under the more stringent federal rules.

Veronica was 27 months old when she was turned over to Brown, and had lived her entire life with the Capobiancos, an important point noted by the South Carolina Supreme Court in its 3-2 decision issued in July 2012.

“It is with a heavy heart that we affirm the family court order,” the majority opinion states. “Because this case involves an Indian child, the ICWA applies and confers conclusive custodial preference to the Indian parent. All of the rest of our determination flows from this reality.”

Justice John Kittredge wrote a blistering minority dissent, saying the court’s ruling disregarded Veronica’s best interests in awarding custody to Brown.

“Today the court decides the fate of a child without regard to her best interests and welfare,” Kittredge wrote. “It is clear to me from the totality of the majority’s analysis that its application of ICWA has eviscerated any meaningful consideration of Baby Girl’s best interests, despite its lip service to this settled principle.”

The Capobiancos, backed by Maldonado, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In written briefs and oral argument, the high court was asked to settle the issues of race, best interests, and equal protection that have divided state courts across the country.

In the end, the court wrote a narrow opinion focusing on the technical language in the law.

Since Brown abandoned Maldonado during pregnancy, and did not have custody of Veronica until she was more than two years old, there was no “continued custody” to protect and no “Indian family” to preserve, Justice Samuel Alito wrote for the 5-4 majority.

“In such a situation, the ‘breakup of the Indian family’ has long since occurred,” Alito wrote.

The court also ruled that, since the Capobiancos were the only family that had formally applied to adopt Veronica, the preferences for placement in an Indian home did not apply.

Dissenting justices based much of their argument on protecting the rights of biological parents, not just Indians. Parental rights in the federal statute are greater than those afforded non-Indian parents in most state laws, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote for the minority. But they are consistent.

Scalia, joining with the minority, put it more succinctly:

“The court’s opinion, it seems to me, needlessly demeans the rights of parenthood,” he wrote. “But parents have their rights, no less than children do.”

CONSTITUTIONAL AVOIDANCE

While the Supreme Court did not resolve the constitutional disputes, it did raise constitutional concerns.

Justice Anthony Kennedy invoked “constitutional avoidance” during oral arguments in asking whether there was a way to “import” best interests of the child protections absent in the law.

Under the legal principle of constitutional avoidance, judges seek ways to apply statutes in a constitutional manner rather than voiding them outright if possible.

Kennedy voted with the majority.

Justice Clarence Thomas also raised constitutional concerns over the Tenth Amendment, which protects the powers of states against unwarranted intrusion by the federal government.

Child welfare cases are historically the domain of states, not the federal government, Thomas wrote.

To justify passing ICWA, Congress invoked a constitutional provision allowing the federal government to regulate commerce with Indian tribes. But adoptions are not “commerce” and Indian children are not “tribes,” Thomas said in his concurring opinion.

“The Constitution does not grant Congress power to override state law whenever that law happens to be applied to Indians,” Thomas wrote. “Accordingly, application of the ICWA to these child custody proceedings would be unconstitutional.”

Thomas said he sided with the majority because it found a “plausible interpretation” of the law that avoided constitutional shortcomings.

Veronica’s case was sent back to the South Carolina courts to make a custody determination without being constrained by the parental protections Brown would have under ICWA.

The South Carolina Supreme Court ordered Veronica returned to the Capobiancos. An interstate custody battle that eventually embroiled the governors and courts of South Carolina and Oklahoma ensued when Brown refused to turn over Veronica to the Capobiancos. He eventually dropped his efforts and she was returned in September 2013. She had just turned four years old.

FRUSTRATED POLICY

Since the Supreme Court’s decision hinged on a technicality over the meaning of “continued” custody, it did little to resolve the sharp divisions over the federal law in state courts.

No issue is more divisive than what is known as the “existing Indian family doctrine,” or EIFD.

The EIFD holds if neither the child nor the parents has any significant connection to an Indian tribe other than race, federal dictates on such things as transferring cases to tribal courts or preferred placement of children in Indian homes do not apply.

The EIFD was born from constitutional avoidance. Almost since ICWA’s passage, judges have struggled to reconcile the unique treatment of Indian children and the special rights of tribes with the child’s constitutional right to be treated the same as non-Indians—the right to equal protection guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment.

When the child’s parents are tribal members living on the reservation and immersed in the Indian culture, as was the circumstance in the 1989 Holyfield case, application of the law is largely jurisdictional. Tribal courts have the power to make custody and placement decisions for tribal citizens.

But for children born off the reservation to parents who never had any significant contact with the tribes, no legitimate purpose is served by having their welfare decided by tribal courts or forcing them to be raised in Indian homes, according to courts that have adopted the EIFD.

ICWA was passed to preserve Indian families and protect tribal rights. But if a child was neither born nor raised in an Indian culture, there is no “existing Indian family” to preserve and no tribal rights to protect, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled in a 1982 case, the first to articulate the EIFD.

At that point, the only justification for invoking the statute is the child’s race, the court found.

That case involved a boy born in January 1981 to a non-Indian mother and a father who was five-eighths Kiowa.

The father had a long history of violent felonies and was in prison when the child was born. He also had spent time in a hospital for the mentally ill or criminally insane.

The mother signed paperwork allowing the child’s adoption the day he was born. But the father challenged the termination of his parental rights under ICWA, aided by the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

“We know of no law anywhere that would require this court or any other court to submit a helpless infant to an environment and standard of custody displayed by this father,” the Kansas Supreme Court said in rejecting the father’s appeal and allowing the child to be adopted by a non-Indian family.

Other courts disagree.

The Kansas Supreme Court reversed itself in 2009, abandoning the EIFD in a custody dispute between a father who was a member of the Cherokee Nation and a non-Indian mother who sought to place her child for adoption. By that time most states were rejecting the doctrine, either through court decisions or through legislation.

Nothing in the language of the act requires the child to have any significant connection to an Indian tribe or culture, the Arizona Court of Appeals ruled in a 2000 case that is frequently cited by critics of the EIFD.

More importantly, the EIFD is contrary to the law’s purpose of protecting Indian tribes, the Arizona court found in a case that still guides Indian child welfare decisions in the state.

“Adopting an existing Indian family exception frustrates the policy of protecting the tribe’s interest in its children,” the Arizona court ruled.

That case involved a child exposed to cocaine in the womb and born with serious medical problems. The mother was a cocaine user. The father, a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation, was in prison but challenged the state’s actions and had the case transferred to tribal court so the child could be placed with an Indian family.

The court’s ruling does not say what happened to the child, identified only as Michael J. Most court decisions in child welfare cases use only first names and do not disclose information about final placements.

CALIFORNIA DIVIDE

The deepest division over the EIFD is in California, the state with the largest Indian population. As of last year, four of the six California appeals courts had rejected the existing Indian family doctrine and two had embraced it. The state Supreme Court has not settled the divide.

The California case that most directly adopts the EIFD involved twin two-year-old girls, identified as Bridget and Lucy, placed for adoption when they were born in November 1993.

Both biological parents initially signed away their parental rights so the adoption could take place. At the time, they lived with their two other children in a Los Angeles suburb.

The twins were raised from birth by an Ohio couple, who filed paperwork to adopt them in May 1994.

By then the birth parents, identified as Richard and Cindy, changed their minds and sought to void their consent to adoption.

Neither the parents nor the children lived on an Indian reservation. Though Richard was three-sixteenths Pomo Indian, he never had any significant involvement with the tribe or the culture. He was not enrolled as a member until after the custody battle began.

Aided by the Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the parents tried to undo the adoption.

Richard and Cindy grew estranged as the custody fight dragged on. Cindy obtained a restraining order alleging that on numerous occasions Richard had assaulted her, pushed her down, and abused their two other children by “picking them up by the neck and shaking or dropping them, poking them in the face, or hitting them on the head.”

In rejecting the attempts to undo the adoption, the California appeals court declared the law would be unconstitutional without an existing Indian family exception.

“To the extent that tribal membership within the meaning of ICWA is based upon social, cultural, or political tribal affiliations, it meets the requirements of equal protection,” the court held. “However, any application of ICWA which is triggered by an Indian child’s genetic heritage, without substantial social, cultural, or political affiliations between the child’s family and a tribal community, is an application based solely, or at least predominantly, upon race and is subject to strict scrutiny under the equal protection clause. If ICWA is applied to such children, such application deprives them of equal protection of the law.”

In 2007, a different California appeals court came to the opposite conclusion and rejected the EIFD.

The child, Vincent, was born in 2002. Two years later, the state removed him from his mother’s custody and placed him in foster care.

At the time, Vincent’s Indian mother, Paz, was a long-time heroin addict living in a substance abuse facility. She had previously lost custody of seven other children, four of whom who were born with drug addictions, and was arrested for being under the influence of heroin while pregnant with Vincent.

Vincent’s father was in prison, where he’d been since 1991. Vincent was apparently conceived during a conjugal visit, according to court records.

Both parents challenged the termination of their custodial rights under ICWA. Two North Dakota tribes got involved on their behalf; the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and the Spirit Lake Sioux tribe.

Spirit Lake is where Laurynn Whiteshield was killed after being placed with her grandfather by the tribal court.

Chippewa officials sought to have the case transferred to tribal court, and stated their intent to place Vincent with an Indian family on the Spirit Lake reservation as a courtesy to the neighboring tribe.

The juvenile court judge invoked the existing Indian family doctrine and rejected the tribe’s request. Vincent did not meet the blood-quantum requirements of the Spirit Lake tribe, and Paz had no connection other than blood to the Chippewas, the judge ruled.

The California Court of Appeals reversed that decision after the parents appealed.

Vincent is an Indian child under the statute’s definition, the appeals court found. Nothing in the law allows the EIFD.

A child has no constitutional right to a stable home, the court said. The fact that for two years Vincent had been well cared for in a foster home was for the tribal court to consider.

‘EIF LITE’

The U.S. Supreme Court was asked by all sides to resolve the dispute over the existing Indian family doctrine in briefs filed in the 2013 case involving Veronica Maldonado.

At that time, 19 states had rejected the EIFD, either through court decisions or legislation, according to court documents and law review articles related to the case. At least five states, including California, had statutes barring the use of the EIFD.

Courts in four states—Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Washington—previously adopted the EIFD, but later abandoned it in subsequent court rulings.

South Carolina explicitly rejected the doctrine when it initially ordered Veronica be sent to live with her father.

Seven states recognized the EIFD through judicial opinions.

Lawyers representing Veronica, her mother, and the Capobiancos argued ICWA is unconstitutional, especially without the EIFD, because it is a race-based law that deprives Indian children and their custodial parents of their rights.

Indian tribes and their supporters argued adopting the doctrine improperly gives state judges the power to determine who is “Indian enough” based on their bloodlines and past involvement in tribal culture. That is something state courts are ill-equipped to decide, said Dawn Williams, chief appeals counsel in the Child and Family Protection Division of the Arizona Attorney General’s Office.

Williams helped represent Arizona and 17 other states in a brief filed with the Supreme Court arguing against adoption of the doctrine.

The high court did not directly address the EIFD in its opinion. Whether it did so indirectly is in dispute.

Rothfeld, who represented Dusten Brown, said Veronica’s case was so fact specific that it will have little practical application outside those narrow circumstances. The justices did not rule on constitutional challenges to the act or the legitimacy of the existing Indian family doctrine, he said.

“It was very clear that five of them were extremely uncomfortable with the factual situation of the case, and I think that’s what drove the decision,” Rothfeld said. “They made a kind of visceral assessment of the factual circumstances and that cleared the approach and the outcome.”

But Fiddler, the lawyer who helped represent Veronica’s adoptive parents in the Supreme Court case, said the language in the decision raises some of the same constitutional concerns that are at the heart of the EIFD controversy.

“The constitutional concerns are definitely in the shadows, but they’re there,” Fiddler said.

He cited a passage in the majority’s opinion that was critical of the South Carolina Supreme Court’s interpretation of the federal statute.

The South Carolina Supreme Court’s decision in favor of Veronica’s father “would put certain vulnerable children at a great disadvantage solely because an ancestor—even a remote one—was an Indian,” Alito wrote in the majority opinion.

“Such an interpretation would raise equal protection concerns.”

That language describes the concept of the EIFD, Fiddler said, calling the court’s ruling “EIF Lite.”

“We didn’t get the EIF adopted, but we got the same result a different way,” Fiddler said.

One California appeals court found otherwise, issuing a decision in August 2014, a year after the Veronica case was decided by the Supreme Court, questioning the validity of the EIFD.

That case involved a girl named Alexandria who is one-sixty-fourth Choctaw. When she was 17 months old, Alexandria was removed from the custody of her mother, who had a lengthy substance abuse problem and had lost custody of six other children. The girl’s father had an extensive criminal history and had also lost custody of another child.

The Choctaw tribe did not object while the girl was in foster care, but when the couple that had raised her for 2½ years sought to adopt, the tribe insisted Alexandria be placed with a distant relative.

The adoptive couple challenged ICWA’s constitutionality and asked that the EIFD be invoked. The California court did not formally decide the constitutional issues for technical reasons, but did signal it would be inclined to reject the doctrine.

New regulations proposed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which would dictate how state judges interpret the statute, specifically ban the use of the EIFD.

“There is no ‘Existing Indian Family Exception’ to ICWA,” the proposed regulations state, reiterating the language from the earlier, non-binding guidelines meant to help state judges interpret the act.

No Happy Endings

As lawyers and judges haggle over legal nuances, Indian children are left in dangerous or temporary homes.

For some, the heightened rules in the law mean that even when there is documented danger, abusive or neglectful parents are given more chances than they would have under state laws governing the decisions affecting non-Indians.

Shayla is one such child.

She was born in 2001. Child protection workers in Nebraska took custody of Shayla and her two younger sisters in 2008, placing them in foster care.

The children’s father, David, had a history of domestic violence and used methamphetamines while caring for the children. A state social worker testified during a juvenile court hearing that leaving the children in David’s care would result in serious physical or emotional damage to the children. The juvenile court judge agreed and ordered the girls to be placed outside the home.

But David is an Indian, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. He appealed, claiming the judge did not hear testimony from an expert on ICWA, as required by the federal law.

The appeals court agreed in 2009 and the children were returned to David.

New allegations of abuse surfaced in 2012, when Shayla showed up at school with a dark bruise on her face. The children were removed from the home again.

They were eventually returned to David, but the state retained legal custody, giving child welfare workers more power to supervise the children’s care.

With the tribe’s backing, David challenged that arrangement, arguing the state had failed to meet the heightened requirements for family reunification under ICWA.

The appeals court agreed in 2014.

Lancaster County officials, who handle child welfare cases, appealed to the Nebraska Supreme Court, which also sided with the father in November 2014. Buried in the court’s analysis is a line saying its decision may be moot because the children were subsequently “removed from David’s physical custody.”

The reason, unstated in the Supreme Court’s decision, is that child welfare workers learned in 2013 that Shayla’s sisters were being molested in the home by two sons of David’s live-in girlfriend, one of whom later alleged in court that he had been molested by David. The abuse of Shayla’s sisters had gone on for at least two years by the time it was reported, according to court records.

ICWA advocates praised the state Supreme Court’s decision, even though it came a year after the molestation allegations surfaced.

David, who was not charged with a crime, continued fighting to regain custody of his daughters. He tried unsuccessfully to have the case transferred to the Rosebud Sioux tribal court.

David denied molesting his girlfriend’s children, but did not deny they had sexually abused his daughters. The girlfriend and her children remained in the home after Shayla and her sisters were removed.

In May 2015, a Lancaster County judge terminated David’s parental rights.

“Particularly given his own children’s ages, special needs, and history of trauma, it is highly unlikely if not impossible that he would ever be in a position to safely parent his minor children,” the judge wrote in her order.

Alicia Henderson, chief deputy of the juvenile division of the Lancaster County Attorney’s Office in Lincoln, Nebraska, said Shayla’s case illustrates how difficult it is for child welfare workers to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that keeping a child in a potentially dangerous home will result in serious physical or emotional harm, as required by the statute.

As a result, children who could be removed from a home under the “clear and convincing” evidence standard of state law sometimes remain with their parents if they are Indians, Henderson said.

“I don’t think it’s ever a happy ending when children experience any kind of abuse in their family home, no matter what kind it is,” Henderson said. “We all know of cases where we believe that something is happening, but we cannot prove it, and it breaks our heart. If you have to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt, you bet it makes it harder.”

LAST OF THE MOHICANS

Even when ICWA challenges do not result in children being sent back to abusive homes, the delays and uncertainty of meeting its procedural requirements can cause harm.

In California, child welfare workers took custody of a girl named Asia in 2004 because her parents exposed her to drugs. Both parents were in prison, and the mother had been arrested while in possession of guns and methamphetamines.

The girl’s mentally deranged father claimed—literally—to be the last of the Mohicans. That was enough to trigger an ICWA inquiry, delaying the permanent placement of Asia and her sibling. The Mohegan Tribe of Connecticut eventually notified the court that it had no interest in the case. It took seven months.

In 2007, the California Court of Appeals reversed a lower court’s decision terminating the parents’ custodial rights and making a girl named Amana eligible for adoption because the law’s notification requirements had not been followed.

Amana was born in 1998 to parents identified in court records as Eddie and Laura. Eddie had been Laura’s pimp and both parents had a long history of drug abuse, child welfare complaints, and criminal arrests.

In 2005, the state took custody of Amana. Eddie was in prison and Laura’s location was unknown. The juvenile court terminated the parents’ custody rights and ordered Amana be eligible for adoption. By then Amana and her two siblings were living in the home of a foster parent who wanted to adopt all three children.

Eddie successfully challenged the termination of his parental rights by invoking ICWA.

In 2006, nearly a year after the state took custody of Amana, Eddie declared he had Indian heritage through the Blackfoot tribe. The appeals court reversed the juvenile judge’s order because there was no evidence the state had attempted to contact the tribe.

The court records do not say whether Eddie regained custody of the children.

No Way Out

Joining a tribe at any time to file an ICWA challenge is allowed in the law. Getting out of a tribe to avoid being subject to the law is not so simple.

An Oklahoma father was in jail when the state took custody of his two-year-old daughter because of neglect and exposure to substance abuse in May 2013. The father was a member of the Cherokee Nation, but objected when the tribe tried to have the girl removed from a non-Indian foster home for placement with an Indian family. She is less than 1 percent Cherokee and had no other connection to the tribe.

The father filed paperwork to relinquish his tribal membership, and any potential membership of his daughter, so ICWA would not apply. The Cherokee Nation refused to recognize his relinquishments of citizenship, claiming both father and daughter remained tribal members.

The Oklahoma Court of Civil Appeals ruled against the tribe in May 2015, allowing the girl to stay in the non-Indian home because it was in her best interest. The decision is contrary to BIA guidelines that say the child’s best interest should not be considered when determining whether there is good cause to deviate from Indian placement preferences. The court called the BIA’s stance “self-serving.”

“We disagree that the good cause determination should not include an independent consideration of the child’s best interests,” the Oklahoma court said. “ICWA has been interpreted and applied in a manner that far exceeds its original purpose. Children who do not have any tribal connection other than biology, oftentimes through distant ancestry, are transferred from stable homes in order to create a tribal connection where none existed before. This often occurs, as in the case at hand, at the expense of the child’s best interest.”

Children in the same household also are treated differently under ICWA, depending on whether they have any Indian ancestry. In 2012, the Oregon Court of Appeals ordered more intensive reunification efforts be made for the Indian father of a child than were required for the child’s half-sibling, who had a different father and no Indian heritage.

The Indian father was in prison at the time for robbery and assault. The mother had a long history of alcohol abuse.

Some courts have found that what’s best for the child is irrelevant to many decisions involving Indian children.

The Texas Court of Appeals ruled in 1995 that the best interest of the child is not a factor in deciding whether to transfer a case to tribal court.

“The question of whether a parent or guardian is abusive, neglectful, or otherwise unfit is irrelevant at this point,” the court ruled. “The utilization of the best interest standard and fact finding made on that basis reflects the Anglo-American legal system’s distrust of Indian legal competence by assuming that an Indian determination would be detrimental to the child.”

The Nebraska Supreme Court, citing the Texas ruling, reached the same conclusion in a 2012 case involving parents with a history of domestic violence and child abandonment. The Omaha Tribe of Nebraska never objected when the children in that case, Zylena and Adrionna, were put in foster care. But when the state sought to sever the parents’ rights and place the children for adoption, the tribe objected and got the case transferred to tribal court.

An Omaha tribal representative testified termination of parental rights is against tribal culture.

Death on the Reservation

‘SHOCKING AND HEINOUS’ DEATH

Having a case decided in tribal courts does not automatically mean the child’s best interests will be ignored. Recent media accounts show some tribes do not hesitate to put Indian children in non-Indian homes.

After National Public Radio produced a three-part series in 2011 suggesting South Dakota child welfare workers and judges were wantonly removing Indian children from their homes and placing them with non-Indian families, the network’s ombudsman investigated complaints the stories were slanted and misleading. The ombudsman, after a year-long investigation, debunked many of the findings in the original series. One fact omitted from the original reports was that about 40 percent of the Indian children put in foster care in the state were put there by tribal judges, and they placed those children in non-Indian homes at even higher rates than non-Indian judges.

State court judges also have forced Indian children back into dangerous homes because of the heightened requirements of the statute, with tragic results.

Declan Stewart was taken from his Indian mother by Oklahoma state officials in January 2006. By then, Declan had sustained numerous injuries including a skull fracture and severe bruising in the area from his testicles to his rectum. State child welfare workers sought to have the mother’s parental rights terminated “based on the shocking and heinous nature of the allegations.” But the Cherokee Nation objected and sought reunification.

The state backed down and Declan was returned to his mother in July 2007. A month later, the five-year-old was beaten to death by the mother’s live-in boyfriend, who was later convicted of murder.

High rates of child abuse, crime, suicides, and poverty, combined with the general shortage of qualified foster and adoptive homes for both Indian and non-Indian children, mean Indian kids are more likely to be left with abusive parents or put in dangerous homes, said Elizabeth Bartholet, faculty director of the Child Advocacy Program at Harvard Law School.

“These strong preferences with placing with Indians and within the tribe, of course, puts kids at risk for being placed with at-risk people,” said Bartholet, author of two books dealing with child abuse, foster care, and adoption. “If you are realistic and not hopelessly romantic, and if you dare to say it, there’s going to be a high percentage of the potential parents who are going to be questionable as foster parents or adoptive parents or biological parents.”

Adjusting to life on the reservation is particularly tough for an Indian child who has never lived in the Indian culture, said Lita Sage DesRochers, a White Mountain Apache who was placed for adoption by her mother shortly after she was born.

DesRochers’ foster parents tried to adopt her in 1977, just before the law took effect. The Apache tribe fought it, and about 1982, when she was five years old, a judge ordered her returned to the tribe for a reservation placement.

The family she was living with went on the run rather than give her up, even though her adoptive father had a thriving drywall and stucco business and the couple had other children. They finally turned themselves in when DesRochers was 12. She was sent to live with her mother on the White Mountain reservation in Arizona.

“I was Apache property that needed to go back to where the Apaches were,” DesRochers said. “I was totally lost. You have a sense of dread. You have the depression. You have even the inkling of suicide. That was really hard to get past. It took a toll.”

DesRochers lived for three years with her mother on the reservation. She said she was never accepted by the other Indian children, who called her “that white girl.”

After a confrontation with her mother when she was 16, DesRochers was sent back to live with her adoptive parents and remains close to them.

SADISTIC VIOLENCE

Other Indian children are not so lucky.

On the Spirit Lake Sioux reservation in North Dakota, children were routinely put into foster homes with registered sex offenders and others with histories of child abuse convictions, according to reports by federal whistleblowers and a 2012 investigation by the New York Times. In one home on the reservation, nine children were under the care of a father, uncle, and grandfather who each was a convicted sex offender, the Times found.

“The crimes are rarely prosecuted, few arrests are made, and people say that because of safety fears and law enforcement’s lack of interest, they no longer report even the most sadistic violence against children,” the Times reported.

Spirit Lake is where the Indian Child Welfare Act originated. In 1968, members of what was then known as the Devils Lake Sioux Tribe were concerned about the large number of reservation children being taken from their homes by local social workers and placed with non-Indian families. The tribe launched a national effort to change child welfare laws, which led to passage of ICWA a decade later.

Scrutiny of the Spirit Lake child welfare system by federal and state authorities began after a 9-year-old girl and a 6-year-old boy were raped, sodomized, and murdered in their father’s home in 2011.

In April 2012, Michael Tilus, the director of behavioral health at Spirit Lake for the U.S. Public Health Service, warned of an “epidemic” of child abuse on the reservation.

Tilus, who was later reprimanded for the disclosure, said he’d tried for years to get someone in the federal government to do something about the abuse, but it “resulted in no agency action.”

Similar concerns were raised in a series of reports beginning in June 2012 by Thomas Sullivan, regional administrator for the Administration for Children and Families at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Sullivan reported almost 100 incidents of child abuse and professional misconduct by officials at the Spirit Lake Tribe and the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the 13 reports he wrote through March 2013.

In October 2012, the tribe voluntarily turned over responsibility for child welfare to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It retained its power over ICWA cases. By then the problems at Spirit Lake had become national news because of the disclosures by Sullivan and Tilus.

Both federal whistleblowers were prevented by their supervisors from testifying at a June 2014 hearing on Spirit Lake abuses by the House Natural Resources subcommittee on Indian affairs, according to subcommittee members.

Joanne Streifel, a Spirit Lake tribal elder and former social worker on the reservation, said tribes too often hide behind words like culture and sovereignty to avoid accountability for failing to protect children from abuse.

Child abuse is not part of the Sioux culture, Streifel said.

“They often use the words ‘our children are sacred and we need to protect them,’” Streifel said. “But I don’t see it happening. They are sacred. If they were sacred like the powers that want to have the recognition (claim), they wouldn’t be put in homes of abusers. They wouldn’t be taken from a nurturing foster home just because they’re non-native, and brought back into this cesspool of alcohol and abuse.”

Myra Pearson, who took over as chairwoman of the Spirit Lake tribe in October 2014, said she cannot explain how things got so bad at Spirit Lake, but that she is committed to protecting children and correcting the problems of the past.

Since the 2012 turnover to the BIA, the tribe has implemented a series of reforms that include requiring prospective foster and adoptive parents to undergo background checks and fingerprinting, Pearson said. It has also hired social workers and other professionals whose job is to protect children.

The priority now, Pearson said, is to ensure endangered children are put into a safe home and not simply placed with an Indian family under the guise of protecting tribal culture.

“We treat these children like they’re knick-knacks,” Pearson said. “I’m willing to admit that it’s our fault. But how do we help them now? How can we help them, to serve them in some way where they can live a decent life?”

The Goldwater Institute contacted a half-dozen of the nation’s largest tribes that are most active in Indian child welfare cases. Pearson was the only tribal leader who agreed to an interview.

DEATH IN A CRISIS

Laurynn Whiteshield and her twin sister were thrown into the chaos at Spirit Lake because of the Indian Child Welfare Act two years ago.

The girls were taken from their biological parents when they were nine months old and placed with Jeanine Kersey-Russell, the minister in Bismarck who raised Laurynn and Michaela until they were just shy of three years old.

When the county, which handles child welfare cases, sought to sever the parents’ rights, the tribe got involved and demanded the children be placed on the reservation.

A tribal judge gave custody of the children to their grandfather, Freeman Whiteshield, on May 7, 2013. Also living in the home was Freeman’s wife, Hope Tomahawk Whiteshield, who had been charged eight previous times with child neglect offenses in tribal court.

On June 12, 2013, the twins were playing outside with Hope Whiteshield’s three children and two other young relatives. Without warning, Hope Whiteshield picked up Michaela and threw her off an embankment. She then did the same with Laurynn.

Michaela was not seriously injured.

Laurynn was breathing but unconscious. Whiteshield took the children inside, bathed the still unresponsive Laurynn and dressed her in pajamas, then put her to bed. The other children were warned by Whiteshield not to tell anyone what happened that day.

The next morning, Laurynn was dead.

Whiteshield later told police she was depressed about having to take care of kids all the time. She was convicted of child abuse resulting in death, and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Michaela was returned to Kersey-Russell.

“She was sweet and quiet and patient and loving,” Kersey-Russell said of Laurynn. “She was a nice little girl.”

Kersey-Russell was not notified of Laurynn’s death. She found out after an Indian couple who had hoped to adopt the twins saw the news reports and began calling family members for information.

“It was devastating,” she said. “It was beyond devastating to think of what the girls had already gone through in their lives before they were nine months old, and what they had gone through in the days since they had been gone.”

If there is any comfort in what happened to Laurynn, it is that her sister is now safe, Kersey-Russell said.

“We know that, heroically, if she had not died, her sister and she would still be stuck there,” Kersey-Russell said. “So she saved her sister’s life.”